Historical musicology has traditionally privileged written items—such as scores, manuscripts, and personal correspondence—as its primary sources, while sound recordings have been relatively overlooked. This tendency is especially pronounced in the study of early music, where performances of repertoires predating the recording era are typically reconstructed through written documentation alone. Recorded sound therefore remains a notably underexplored resource in early music research.

The Short-Term Scientific Mission (STSM), hosted by Eva Moreda Rodríguez at the University of Glasgow in June 2025, set out to address this imbalance by initiating the development of a database dedicated to early music recordings. The project brought together researchers Áurea Dominguez (Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Switzerland) and Arash Ahmadzadeh (Breuillet Conservatory, France), with the shared aim of increasing scholarly access to this underexplored body of material. At the heart of the mission was a critical interrogation of foundational questions: What constitutes “early music”? What defines an “early recording”? And where should chronological boundaries be drawn for inclusion? These are not simply practical considerations but also interpretive ones, as they shape the epistemological structure and research potential of the database. While inherently subjective, clarifying such definitions is crucial for ensuring methodological coherence, transparency, and scholarly rigor.

Building on these initial questions, our first discussions during the research visit focused on how to define “early music” and “early recordings” in a way that reflects both historical usage and contemporary research needs. While existing frameworks such as EarlyMuse use 1914 as a general cutoff, we recognized that “early music” is not strictly a matter of chronology or repertoire. Its meaning has been shaped by the twentieth-century Early Music movement, where historically informed performance practices introduced new ways of engaging with older works. A recording of Bach, for example, may reflect radically different interpretive choices depending on the approach. To keep the database inclusive and analytically useful, we decided to focus on music composed before 1800, regardless of performance style. Similarly, we defined “early recordings” as those made before the advent of LP (long-play) technology in 1947. While arbitrary in some respects, these boundaries provide structure while allowing for a broad range of research perspectives, from performance practice to reception history.

As one of the intended outcomes of the STSM is a jointly authored academic article, significant time was devoted during daily meetings to developing its structure, arguments, and central research questions. In parallel, each participant undertook focused work on a specific format of early sound recording, resulting in the creation of three “mini-databases” aligned with their respective interests and expertise. These comprised phonograph cylinders, piano rolls, and 78rpm disc recordings. This distributed yet collaborative approach not only allowed the team to test and refine shared methodological principles, but also underscored the diversity and complexity inherent in early recording media.

Over the course of the STSM, several key challenges emerged, shaping both the database’s design and its broader scholarly implications. Epistemologically, many existing catalogues and discographies—such as those by Henri Chamoux, John Bolig, and the City of London Phonograph and Gramophone Society—were compiled for specialist audiences and remain opaque or inaccessible to a wider research community. Practical and technical challenges further complicated the work. While relying on existing compilations can expedite data gathering, it risks perpetuating inaccuracies or omissions. More rigorous methods—such as cross-referencing primary sources like original catalogues—offer greater accuracy but are significantly more labor-intensive. Decisions regarding metadata granularity, such as the inclusion of performer roles, instrumentation, or cylinder types, directly influence the richness and usability of the database. Another major concern is the issue of digitization bias: a large portion of early recordings remains undigitized, meaning that a reliance on online or digital sources alone would inevitably skew the data. Finally, classification systems—whether by genre, function, or content—present further conceptual hurdles that require thoughtful resolution, as they directly affect how the database will be navigated and interpreted by future users.

The Database: Design, Scope, and Scholarly Relevance

From the outset, we recognized the need to balance specialist precision with broader accessibility. Potential users of the database include not only musicologists, but also researchers from diverse disciplines. While some may search for specific recordings, others might explore broader patterns. With this range of use cases in mind—and drawing on existing catalogues—we developed a prototype designed to support both scholarly inquiry and practical applications, rather than serving academic musicologists alone.

This inclusive approach shaped a key principle of the project. Rather than limiting entries to digitized recordings, we aimed to document all known early recordings, regardless of current accessibility. Excluding non-digitized materials would risk reinforcing a distorted view of the historical record—one shaped more by preservation and digitization trends than by actual historical activity.

The final schema balances consistency, clarity, and flexibility, anticipating the needs of a diverse user base. Fields include:

- Title 1: The specific title of the piece recorded (e.g., aria or instrumental movement).

- Title 2 / “Part of”: The larger work the piece belongs to (e.g., symphony, suite, opera), capturing contextual relationships.

- Composer: Standardized composer name to ensure consistency (e.g., “Johann Sebastian Bach” rather than localized variants).

- Performer: Main performer(s), including ensemble names where relevant.

- Instrument: Instrument or voice type heard in the recording, not necessarily the original instrumentation.

- Manufacturer/Label: The company or brand that produced the recording.

- Series: The series name under which the recording was issued, if applicable.

- Matrix Number: Identifies the master recording.

- Catalogue Number: The label’s commercial release number.

- Recording Date

- Recording Location

- Format: Recording medium—cylinder, disc, or piano roll.

- Media Type: More specific categorization within the format (e.g., “Concert” or “Standard” cylinder).

- Reference: Source used to verify the recording (e.g., Chamoux, CLPGS), ensuring transparency.

- Digitisation: Link to an online version of the recording, if available (e.g., DAHR, Phonobase).

- Notes: Additional context—e.g., genre, performance style, arrangements, or interpretive comments.

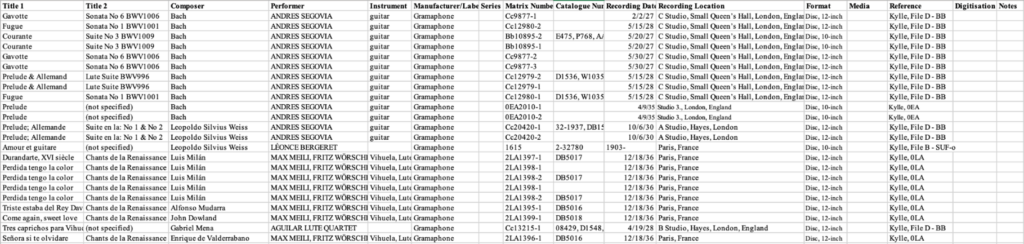

As noted, this database is designed to serve a broad community of researchers with varied questions and aims. A musicologist, for instance, might explore from the present prototype (Figure 2) when historically informed performance practices began influencing recording choices—for example, identifying when Luis de Milán’s music began to appear on vihuela or lute rather than modern guitar. Performance-practice questions, such as tempo, ornamentation, or phrasing may also be studied. But the database’s relevance extends well beyond traditional musicology. Scholars in media history, sound studies, reception theory, or canon formation might ask: Why did early recording companies prioritize composers like Bach or Milán? What role did labels like Gramophone play in shaping the early music canon? How did studio practices or technical constraints influence interpretation and repertoire?

In short, this database is not only a resource for tracing early music’s recorded history—it also opens pathways into interdisciplinary research on the cultural, technological, and institutional forces that defined the early recording era.

Next steps

With the foundations now in place, the next steps for the project focus on refining, expanding, and communicating our work. The week-long research visit clarified key definitions and methodological decisions. Now the challenge is to translate that clarity into sustained development, broader visibility, and scholarly contribution. The most immediate task is drafting a detailed proposal that documents the metadata schema, repertoire boundaries, and cataloguing reasoning. This proposal will serve several purposes: it will guide future collaborators, inform technical development, and support conversations with institutions such as RISM. This stage is essential not only for internal coherence but also for anchoring the project within ongoing conversations in music documentation in the frame of digital humanities.

In parallel, we will finalize and share selected examples from the pilot databases. These examples will illustrate how the database functions across different types of historical recoded media and will offer a tangible preview of the project’s broader potential. Each mini-database focuses respectively on cylinders, 78 rpm discs, and piano rolls, and draws on different materials, sources, and documentation strategies (see figure 3). This diversity allowed us to examine how the same structural framework could adapt to the unique challenges presented by each format. For instance, piano rolls often lack standardized metadata, while cylinders might be poorly documented or only partially preserved. Discs, although sometimes better catalogued, come with their own variations in labeling and classification. By applying our metadata schema across these contrasting formats, we could test its flexibility, identify inconsistencies, and refine how we capture essential details such as performer, instrumentation, and recording context. These pilot projects not only helped validate the structure of the database, but they also underscored the need to account for material and historical differences in early recording technologies. The examples we select for public sharing will reflect this range, offering both practical entries and a demonstration of the critical cases the database is designed to support.

Looking further ahead, one of the central outcomes of the STSM visit will take the form of a scholarly publication. This piece will explore the theoretical framework behind the database, examine the logic of the metadata structure, and consider the broader research implications of cataloguing early recordings of early repertoire. Rather than presenting a finished product, it will offer a critical reflection on the process, highlighting methodological choices and opening space for dialogue about the place of recorded sound in early music studies. For this objective, the team is focusing on journals with audiences in musicology, recording history, and digital humanities.

We also identified key areas for medium-term development. One is community engagement. While the initial database is curated by a small research team, we are exploring ways to eventually include contributions from a wider group of scholars and enthusiasts. This could take the form of user-submitted entries, crowdsourced metadata verification, or thematic collaborations focused on particular repertoires or formats. Sustaining and expanding the project will also require funding. We plan to identify relevant calls in digital heritage, archival research, and interdisciplinary musicology. Building a flexible yet robust technical infrastructure, ideally open-access and adaptable to future formats, will be one of the priorities for any follow-up funding initiative, creating space for interoperability with other kinds of resources.

What began as a focused research mission has grown into a wider intellectual project. By positioning recorded sound at the center of early music studies, we hope to challenge conventional hierarchies of sources and open new lines of inquiry across disciplines. The STSM has launched a strong collaborative foundation. The next steps will shape how the database evolves, who uses it, and how it contributes to a more inclusive and materially grounded history of early music.